So here are some things I’ve been thinking about this week.

In the beginning was the essay prompt

To1 dramatically and intentionally oversimplify the course of post-Cold-War human history, for the past 20+ years, the most powerful thing you could do with text, in some senses at least, was to write computer code with it.2 After all, computer code (as humans normally write it) is nothing but a very particular dialect of basically English3 that is pedantically interpreted by lower-level software into a very particular string of 1s and 0s. And we’ve given it the ability to make things happen with stuff in the real world, stuff like money, and how to call a taxi cab, and how to watch the news, and who people date, and what they find funny, and where they go on vacation, and who they vote for, and did I mention money.

This is, of course, a huge divergence from the vast majority of human history (again, oversimplifying with a wild abandon and angering several of you with advanced degrees), where the best way to command things in the real world while writing very pedantically was to be a bureaucrat, or a clergymember, banker, or, lawyer (but I repeat myself).

For much of human history, the best way for an ambitious striver parent to get their child into a better life was, basically, writing really really good essays.4 Of course, the most crisp example of this is the imperial civil service examination structure in China, but don’t kid yourself: it exists everywhere in our modern American culture. As I’ve written before, while my middle and high school’s mission was ostensibly to teach people how to work in industry, the built-in power of high-prestige professional jobs (in law, finance and consulting, and medicine) was such that most students at my school went into those, instead, even if their parents were so staggeringly wealthy5 they never had to work a day in their lives.

Writing has power over humans. We use it to organize our society, make plans, bind the past and future together. We run entire institutions in our society through, basically, mass essay writing and copy-editing. What is a law, after all, but a mass of tracked changes backed up by force? What is a regulator, after all, but a bunch of people shuffling documents back and forth until they suit internal and external standards? What is a bank, but a bunch of spreadsheets attempting to write a very specific description of the future? And despite a few recent technical advances, most of it is still shockingly manual, requiring junior staff working late hours in apprenticeship to learn those particular styles of writing, with more senior leaders overseeing them. The writing of medieval theologians rhymes with modern lawyers; the business correspondence of merchants in 1750 BCE could be taken from an eBay feedback page.

Well, what happens when that’s no longer true?

Then came the psychedelic sheepdogs

For those less familiar, the past several months have seen a flourishing in artificial intelligence technology that can, well, create stuff.6 You may already be familiar with image-based AI models like DALL-E 2 that could create cool art from a text prompt, like “A macro 35mm photo of the 11th Doctor Who and his Tardis” that it will generate without any human intervention or real-world objects:

The difference between this era of AI and previous ones is that we seem to have surprisingly stumbled across the ability to ingest massive amounts of data and use it to train (i.e., create and tweak) a relatively small-scale model that is capable of producing outputs that look, well, realistic-enough given a prompt. And just like in some sense DALL-E 2’s model has some ability to translate a phrase into a photo, there are text-based tools, like the recently-announced ChatGPT.

DALL-E 2 is cool, but in some sense not that surprising; after all, we already have image compression algorithms that can turn a big photo into a small one, so it’s not that weird that we can figure out what clumps of pixels are likely to be correlated with each other in lots of image files and then reproduce them (even if the first results of DALL-E 2’s predecessors looked like psychedelic sheepdogs since they were trained on a dataset of dog photos…)

But it should blow your mind that we can do this with words and facts, such that you can make a chatbot that doesn’t suck. ChatGPT, in the words of its creators at OpenAI, “Interacts in a conversational way. The dialogue format makes it possible for ChatGPT to answer followup questions, admit its mistakes, challenge incorrect premises, and reject inappropriate requests.”

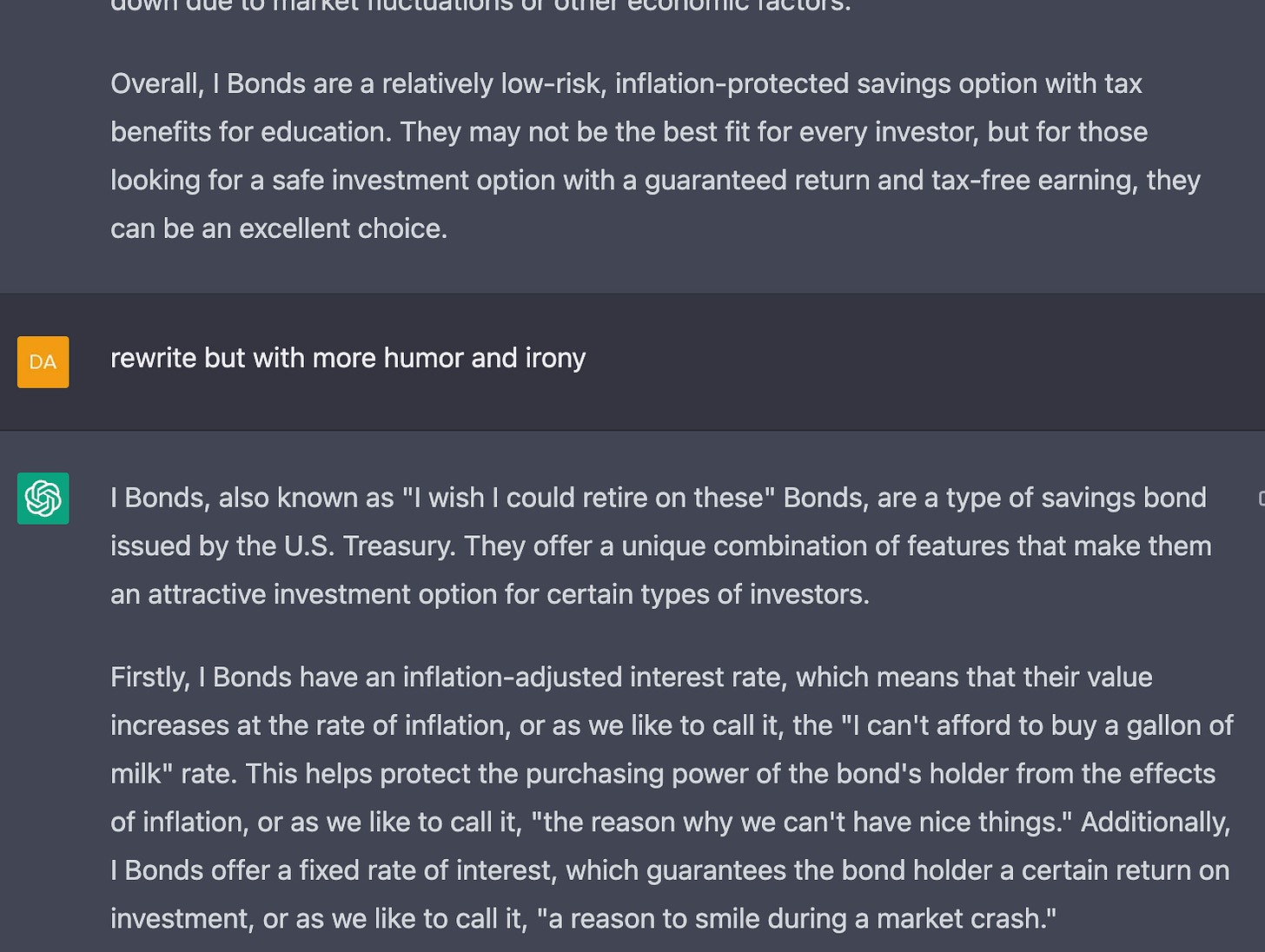

For example, here is an excerpt of a discussion I had with ChatGPT about how to explain one of the most dry concepts in the world — why you should buy US Government I Bonds — in a funny way:

If you haven’t tried it, you really should. While deeply imperfect, it is an incredible “bicycle for the mind” — people are using ChatGPT (and other very similar technologies built by competitors) to do things ranging from asking it to write computer code to negotiate cable bills to composing poems to enabling you to talk with a simulation of a dead famous person. Think of it as being the incredibly grown up and actually useful version of gmail autocomplete: it can, with a little, conversational ask, produce stuff you can use with very little tweaking.

In other words: ChatGPT is now available for staffing as a junior associate on your team, if you want it.

Should you be surprised by this sudden development? Yes, you should be surprised by this, because even many very smart experts were:

Now, this level of excitement may sound to those less familiar like the hype around cryptocurrencies / “Web3”, last year’s trend. I think it’s different; crypto had one very impactful use case (evading nation-state monetary controls), that it excelled at, but then stalled out finding any other real use cases. By contrast, I’d argue that ChatGPT (and similar AI advances) offer value across a really wide range of use cases already. Personally, I’m already using it to write at least one thing each day and expect that pace to increase as it gets integrated more directly into tools I use every day (like Microsoft Office).

So, what does this mean for the consultants?

In addition to the above use cases, one less-important, but funny-to-me, use case of ChatGPT is to help people dunk on management consulting7:

And look, there’s sadly a ring of truth there. Consultants can sound like robots. Among other things, you're paying for the best-in-class advice, so of course that sounds like statistically-averaged jargon sometimes. Beyond that, the nature of consulting is working with senior leaders that are often jockeying for position within organizations; that means that you’re speaking the language of power. The language of power, for better or worse, is famously indirect.8 But even with that excuse, it's totally true that consultants sometimes don't live up to their own stated values when it comes to knowing their clients like real humans. So, fair enough.

But overall, I think this means (and prepare to groan), that management consultants are about to get even more valuable to the economy.

So, what changes will consultants actually have as a result of ChatGPT and its descendants? Here’s a way to think about it: search engines meant that the cost of searching for a specific and detailed string of text e.g., “critiques of the Melian Dialogue from Marxist historians”) was as low as the cost of searching for a generic topic (e.g., “the Peloponnesian War”) used to be. Similarly, ChatGPT means that the cost of producing customized, formatted, specific text at arbitrary length is now as low as the cost of producing generic text at short length.

Why is this so powerful? Honestly, I’ve been trying (and failing) to articulate that for weeks. I’ve talked to lots of people, and honestly, it’s a little like trying to pitch the concept of writing to someone: it’s hard to talk about it in a way that it is sufficiently specific to understand, while still broad enough to convey its general-purpose power.9

Well, after weeks of after weeks of trying to figure out to articulate this idea, someone else just Tweeted it out:

(If this is still a little confusing — “wordcel” is from a meme among those terminally online, that there is a conflict brewing between the writers and bureaucrats [“wordcels”] and the builders of technology [“shape rotators”].)

So, let’s take a step back. Consultants are people that — to at least some degree — excel at writing structured prose about potential solutions to business problems. That prose now will be able to do things directly — not by convincing humans to do work, but by instructing machines to do that work for us directly.

Some of those things will be basic; in particular, Microsoft has said that they’re integrating ChatGPT into the Office products suite, so some of these tools will simply become part of the background learning-how-to-use-Microsoft-products-real-good acculturation that every new analyst has.10 As a result, you can expect the lifecycle of a partner commenting on a draft of a deck to the completion of those edits to shrink meaningfully (heck, you may even be able to then ask ChatGPT, "based on your ingested database of that partner's last 10K emails, what feedback would they then give on this v2 draft?"). That alone will mean that even if consulting work doesn’t transform, it will still be made more efficient — that’s a good thing.

Others might be more impactful. See, people think consulting is about one genius shouting something like, “"You're not in the retail business, you're in the real estate business,” but all-too-often, it’s about a bunch of sleep-deprived, slightly-too-committed, overfocused people working hard on a boring and long list of dozens to-dos to try to help their client do something, like launch a new business or turn around a broken one. A sufficiently-trained AI model could, in success, write the code, business documents, processes, etc. that they’d need to accomplish significant chunks of that work, leaving the remaining hard stuff to the humans.

Of course, here’s the trick about consulting: half the people leave after a few years. And so even if you think you’ve figured out how to train your people better than any other organization on how to leverage ChatGPT and similar tools (as consultancies think reasonably today that they’ve done with PowerPoint, and Excel, and ways of working with them) , soon enough those same skills will be broadly dispersed throughout the world.

And then that’s when things get really exciting.

Don’t get me wrong: there are many, many pitfalls ahead. ChatGPT is still terrifyingly immature, and has failure states we don’t understand well. It’s certainly not ready for any safety-critical work; similarly, the risk that other writers have already written at length about of ChatGPT “hallucinating” — coming up with plausible-sounding but factually baseless statements — is of particular concern for expertise-driven work. And in the longer term, what happens when ChatGPT makes it easier to command an AI to make edits than give feedback to a junior analyst; does the entire apprenticeship pipeline break?

But for now, I’m much more optimistic about the promise of these AI technologies than their perils. And if I’m wrong, well, Kent Brockman said it well:

As a final note — I’ve recently lost my job at the startup I’d joined. I’m looking for new opportunities; I’ve been especially successful in the past in corporate strategy and risk-related roles where I am expected to work closely with technical, product and legal experts, and am looking for similar for my next role. I’m open to a range of different industries, but am especially interested in organizations where I can help keep people safe from bad guys, and/or help them get easier access to government services and benefits that they deserve. Consider this my first ad on this newsletter ever: if you’re aware of an interesting opportunity, I’d love to chat with you and learn more.

Disclosures:

Views are my own and do not represent those of current or former clients, employers, or friends.

I may on occasion use Amazon Affiliate or similar links when referencing things I’d tell you about anyways. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases; I donate the proceeds to charity. While Substack has a paid subscription option, I don’t have any plans to use it at this time.

To credit an inspiration: this title, but not really this essay, is blatantly riffing off of In the Beginning…was the Command Line (Amazon link) by Neal Stephenson.

Okay, and yes, in some 100-ish year period prior to that, engineers and scientists played a similar role; I’m, again, oversimplifying here for the sake of argument. I know that this gun is loaded and that I’m pointing it dangerously close to my own foot.

For better or worse, there aren’t really many “translations” of the basic functions of a given programming language into other human languages, so even foreign-language coders write halfway in English. Generally speaking, when a programmer needs to print something, they write “print” in their code regardless of what country they were born in. When they’re writing something more custom — think a German software engineer writing a unique function to handle a custom data structure for a credit card that only exists in Germany — of course, they’re more likely to choose names for that function and data structure that are in German, of course.

This is serious business; there’s a horrifying truth in the fact that the most terrifying thing that Lavrentiy Beria can say in The Death of Stalin is “I’ve got documents, I have documents on all of you.”

This is comedic business: documents are biased, but still tell us hilarious and embarrassing things. The crowning experience of my seven years of studying Latin was close study of a court speech by Cicero in 56 BCE defending one of his students that sheds light equally on a) Roman factional politics and b) the scandalous escapades of the poet Catullus.

I went to school with several sons of bank presidents. Cleveland is a true case study in the power of the Federal Reserve to sustain local financial institutions.

For this section in particular, as well as his helpful comments on a previous draft, I’d like to thank @nonmayorpete ; sign up for his new daily AI roundup newsletter!

Reminder! This is not a statement on behalf of my former employer in any way, and they might disagree with any or all of this.

Charlie Stross proposes, in his book Dark State (Amazon link) that this approach is a mistake of Western capitalist democracies which can make them psychopathic when pushed in extremis. He thinks it would be healthier if we called things as they were: “Ministry of War” instead of “Department of Defense,” or “Counting Other Peoples’ Murdered Children” instead of “Collateral Damage.” I don’t know if this is actually possible, but sometimes I think that would be better.

For example, an entire previous draft of this essay had what I now think is a digression — albeit an interesting one! — about how ChatGPT might empower an example consulting use case. I think that’s interesting, and might publish it at some point, but probably slightly outside the scope here.

And yes, if you think Microsoft doesn’t force product integration on even its most risk-averse enterprise clients…well, ask any regulated industry how easy it is to turn off Teams from their Office365 subscription.