Hi,

So here are some things I’ve been thinking about this week.

So it turns out the world is a narrow street corner, and the important thing is not to be afraid

(With apologies to Reb Nachman of Breslov)

This past week was Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement / rehearsing conceptually for your death / wearing white / being hangry.

I think it’s fair to say that the vast majority of Jews in America still had an unusual experience with their High Holidays this year, after strong hopes that this year would be Back to Normal.1 And as it’s the official “reflect on everything in your past year and atone for where you missed the mark” day, it’s already a, well, weird day for many folks. But in some ways, though, I think the disjunction of this year made for a unique experience that I’m still reflecting on.2

Unlike many American Jews, I’m not so sure that I have expectations about what Yom Kippur “should” look like — I didn’t really begin observing it (as opposed to just staying home from school) until I was a freshman in college.3 And in my years since then, I’ve bounced between a few different cities, observances, and congregations.

But in general, there are some patterns that are, well, quite literally built into how Jewish communities observe the High Holidays.

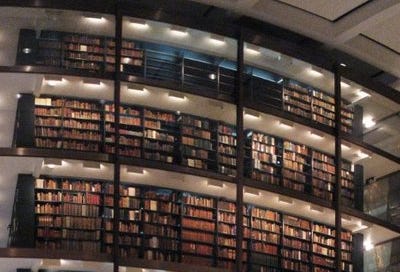

As Sarna4 observes, American congregations have long been famous for having far greater attendance on the High Holidays than the rest of the year. In 19th-century America, your synagogue membership was often quite literally linked to the physical seat that you’d have at the High Holidays, like getting the playoff tickets bundled in with your season tickets package. Similarly, in post-World-War-II America, the characteristic synagogue design (aside from the parking lot) is a building with a “social hall” or similar directly outside the synagogue’s sanctuary, so that the doors can be pulled open wide and overflow seating put in for two days a year, without making the sanctuary feel echoingly too big the rest of the year.5 In other words, being creative with the built environment to pack in the pews is traditional.

Of course, this year has been an unusual challenge to that pattern. Community responses have varied a lot, and I’m not judging — just to take one factor, you can think of many good reasons why a historically-conserved building in one community might have different ability to implement air filtration than a more modern building in another — and my particular synagogue did a bit of all of them.6 They took advantage of both their parking lot7 and their front steps for outdoor tenting, as well as holding masked overflow services inside (at about 50% capacity) when it was raining or for those who couldn’t handle the heat or humidity.

And so, I find myself, on Erev Yom Kippur, sitting in a tent, facing in fact West, on the front steps of Adas Israel synagogue, in the triangular corner slice of land they have between two streets.

Let me be clear: the acoustics were terrible. You’ve got the magnetometers beeping at the doors to keep people safe, buses pulling up alongside with air brakes hissing, ambulances and fire trucks with sirens blaring from the station down the street. The prayer leader has to pause, the minyan has to push its singing louder. But in some ways, that made it perfect.

You see, Judaism is, to some extent, an effort to be awake, to actually respond to the world. If you believe you should say that G-d is blessed for making grapes, lunar months, or special occasions, maybe you’ll be more likely to notice those things as important, and real, and meaningful.

So if you’re focused on the world, and your place in it, and avoiding missing the mark, maybe a visceral, continuous reminder that the world is messy and loud and broken — and that you can do something to impact it — is exactly what you need.

Shana tovah.

Disclosures:

Views are my own and do not represent those of current or former clients, employers, friends, or my cat.

I may on occasion use Amazon Affiliate or similar links when referencing things I’d tell you about anyways. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases; I donate the proceeds to charity. While Substack has a paid subscription option, I don’t have any plans to use it at this time and anyone who gets this newsletter now surely won’t be ever paying for their subscription.

From casual awareness of how many recipients of this newsletter observed the holidays, I am doubly conscious of this fact.

In case you somehow missed all my “fight COVID” newsletters in the past, let me be clear — obviously I hope we fully crush COVID as soon as possible, and I don’t think this is a silver lining that in any way makes up for our failures to fight COVID with all our effort.

I could write more about how I came to deeper religious practice, or I could just tell you to go read Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg’s Surprised by G-d and assume that it was a less cool version of that story, more or less.

The magisterial historian of American Jewry, Jonathan D. Sarna, that is. Not sarna.net, my preferred wiki for information about the fighting robots of the Inner Sphere and their enemies, the Clans.

(This comes up more often than you’d think in my life.)

I often wonder if this was, unintentionally, an implicit subsidy for the rise of the bar and bat mitzvah as a big party instead of just a minor religious occasion. After all, we’ve got this whole social hall right here already, might as well use it…

Dear future Jewish historian using this as a primary source to explain how COVID affected Jewish practices — good luck, I guess?

Somewhere, some elderly rabbi who argued for the driving teshuva is no doubt smugly smiling about how this means that pikuach nefesh is now on his side…